"...the metals are all, in essence, composed of mercury combined and coagulated with sulphur..."

- Geber -

- Geber -

Arabic/Persian Alchemy

The ouroboros represents alchemy's cyclical nature.

While the Greeks certainly spread alchemy to the vast majority of Western Europe, it was the Arabs who dominated in the field. But let it not be said that they were uninfluenced by the Greeks. In fact, the Arabs respected Greek learning, in times even coveting the recipes and literature spread by the Greek alchemists (Greek fire being one, the Emerald Tablet as another).

As the Arabs continued to dominate across the continents, their knowledge of the secret arts grew. At some point they even began unearthing wisdom from the ancient Syrian and Mesopotamian empires. In Baghdad (now the capital of Iraq), the Arabs furthered their learning in what they began calling "the art of khemeia," or "al-chemia," to a point where they even grew a language of their own. If we were looking for the origin of the words "alkali," "algebra," "algorithm," and "alcohol," be assured that the Arabic learners and alchemists had a hand in the construction.

Alchemy's Central Core

I mentioned the Emerald Tablet once or twice in previous lessons, considering that this piece of literature is Egyptian in origin, though Grecian in proliferation. That said, I have included a further discussion of the Tablet in this lesson because the Emerald Tablet is the core in which Arabic alchemy is based.

Arabic alchemists were focused on transmuting the baser metals into gold, though they did not forget that medicine was also an important part of al-chemia. While the Greeks sought to unify philosophical thinking with alchemy, the Arabs began their focus closer to practical, scientific thinking. It is this thought process that led the Arabs to a priority change: transmuting metals to gold began to play second fiddle to creating the "al-iksir", or the "elixir." The Elixir was the Arabs' later goal, for it was believed to hold the remedy to every disease (a panacea). The Elixir also gave eternal youth or immortality, something the Chinese have long sought through their alchemical studies. That said, transmutation was not far from their minds, because the Arabs also believed that this Elixir would have the property of turning any metal to gold.

As the Arabs continued to dominate across the continents, their knowledge of the secret arts grew. At some point they even began unearthing wisdom from the ancient Syrian and Mesopotamian empires. In Baghdad (now the capital of Iraq), the Arabs furthered their learning in what they began calling "the art of khemeia," or "al-chemia," to a point where they even grew a language of their own. If we were looking for the origin of the words "alkali," "algebra," "algorithm," and "alcohol," be assured that the Arabic learners and alchemists had a hand in the construction.

Alchemy's Central Core

I mentioned the Emerald Tablet once or twice in previous lessons, considering that this piece of literature is Egyptian in origin, though Grecian in proliferation. That said, I have included a further discussion of the Tablet in this lesson because the Emerald Tablet is the core in which Arabic alchemy is based.

Arabic alchemists were focused on transmuting the baser metals into gold, though they did not forget that medicine was also an important part of al-chemia. While the Greeks sought to unify philosophical thinking with alchemy, the Arabs began their focus closer to practical, scientific thinking. It is this thought process that led the Arabs to a priority change: transmuting metals to gold began to play second fiddle to creating the "al-iksir", or the "elixir." The Elixir was the Arabs' later goal, for it was believed to hold the remedy to every disease (a panacea). The Elixir also gave eternal youth or immortality, something the Chinese have long sought through their alchemical studies. That said, transmutation was not far from their minds, because the Arabs also believed that this Elixir would have the property of turning any metal to gold.

Balance and Disbelief

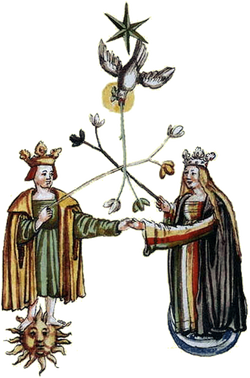

Depiction of the chemical wedding.

Keeping in line with the Arabic/Islamic alchemy that had since taken over the alchemic movement, I'm going to briefly talk about two particular alchemists who have made great contributions in the art.

Balance: Jabir ibn Hayyan

Jabir ibn Hayyan, or Geber, lived during a prolific time in Arabia. For one, he was a contemporary alchemist during the time of Harun ar-Rashid, or Aaron the Upright, the caliph whose name became linked to Scheherazade of the One Thousand and One Nights. But I digress.

It's been a common belief through the many cultures that there is this importance in an alchemical balance. The Chinese have their Yin and Yang, the Greeks their elemental balances. Through Greek influence, the Arabs derived the chemical wedding, a balancing process found in the Emerald Tablet.

To successfully conduct a chemical wedding, an alchemist must be mindful of many conditions. First of all, mercury and sulphur must be mixed within an exact proportion of each other. Secondly, the preparation of such a marriage can only be accomplished during a particular time period. Because of the natural elements involved within the works of alchemy, many alchemists believed that Nature herself played a role, and keeping to the seasons, solar and lunar cycles, and natural conditions is an important part in creating a perfect wedding of the elements.

With this in mind, Geber modified Aristotle's four elements by scientifically applying the balance specifically to metals. In his discourses of alchemy, Geber believed that all the metals were formed by a combination of sulphur and mercury. Sulphur is the "stone which burns," and is considered the combustible element, whereas mercury is the metal. When combined and catalyzed--like Zosimos, Geber believed in such a catalyzing reaction--mercury and sulphur could be married to create gold, or the Elixir.

Disbelief: Ibn Sina

Ibn Sina, or Avicenna, was an interesting non-alchemist. Considered the father of medicine, Avicenna possessed an interesting belief system, mostly the opposite of what many of his contemporaries held during his time period. For one, he heavily believed that medicine itself was a science, not the mystic art that alchemy made it out to be. While he was inspired by Rhazes (who we will talk about in a bit), he took his beliefs further by stating that only science could possibly explain curing illnesses.

It was Avicenna's belief that chemical combinations were the answer to curing ailments, not herbs and stories of a fabled Elixir. During his lifetime, Avicenna managed to compile an encyclopedic list of chemicals, the effects of said chemicals, and the types of ailments these chemicals cured. Furthermore, he was among a faction of scholars who believed that the Elixir was an impossibility. Transmutation of metal into gold was impossible, and therefore merely a subject of alchemical legend.

Balance: Jabir ibn Hayyan

Jabir ibn Hayyan, or Geber, lived during a prolific time in Arabia. For one, he was a contemporary alchemist during the time of Harun ar-Rashid, or Aaron the Upright, the caliph whose name became linked to Scheherazade of the One Thousand and One Nights. But I digress.

It's been a common belief through the many cultures that there is this importance in an alchemical balance. The Chinese have their Yin and Yang, the Greeks their elemental balances. Through Greek influence, the Arabs derived the chemical wedding, a balancing process found in the Emerald Tablet.

To successfully conduct a chemical wedding, an alchemist must be mindful of many conditions. First of all, mercury and sulphur must be mixed within an exact proportion of each other. Secondly, the preparation of such a marriage can only be accomplished during a particular time period. Because of the natural elements involved within the works of alchemy, many alchemists believed that Nature herself played a role, and keeping to the seasons, solar and lunar cycles, and natural conditions is an important part in creating a perfect wedding of the elements.

With this in mind, Geber modified Aristotle's four elements by scientifically applying the balance specifically to metals. In his discourses of alchemy, Geber believed that all the metals were formed by a combination of sulphur and mercury. Sulphur is the "stone which burns," and is considered the combustible element, whereas mercury is the metal. When combined and catalyzed--like Zosimos, Geber believed in such a catalyzing reaction--mercury and sulphur could be married to create gold, or the Elixir.

Disbelief: Ibn Sina

Ibn Sina, or Avicenna, was an interesting non-alchemist. Considered the father of medicine, Avicenna possessed an interesting belief system, mostly the opposite of what many of his contemporaries held during his time period. For one, he heavily believed that medicine itself was a science, not the mystic art that alchemy made it out to be. While he was inspired by Rhazes (who we will talk about in a bit), he took his beliefs further by stating that only science could possibly explain curing illnesses.

It was Avicenna's belief that chemical combinations were the answer to curing ailments, not herbs and stories of a fabled Elixir. During his lifetime, Avicenna managed to compile an encyclopedic list of chemicals, the effects of said chemicals, and the types of ailments these chemicals cured. Furthermore, he was among a faction of scholars who believed that the Elixir was an impossibility. Transmutation of metal into gold was impossible, and therefore merely a subject of alchemical legend.

"I understand alchemy and I have been working on the characteristic properties of metals for an extended time. However, it still has not turned out to be evident to me, how one can transmute gold from copper. Despite the research from the ancient scientists done over the past centuries, there has been no answer. I very much doubt if it is possible..."

- Rhazes -

- Rhazes -

Alchemist Spotlight: Rhazes

Depiction of Rhazes

Muhammad ibn Zakariya Razi, or Rhazes, was perhaps one of the best-known of the Persian alchemists during the Islamic Golden Age. Known mostly as Rhazes, he took the classification and division of alchemical substances to a greater level, creating divisions, including mineral, which he further divided into six categories.

The Major Divisions

The Six Minerals

And from these mineral categories, Rhazes further classified them according to their colors and other characteristics. Pretty comprehensive, huh?

Similar to Avicenna, Rhazes focused on the practicality of his studies. The difference between him and his medicinal contemporary, however, is his main focus, which was still alchemy. Like Avicenna, he did not accept the theory of balance like Geber did. Unlike Avicenna, he believed that the transmutation of metals can still be achieved (though, after some work in attempting to create the Elixir, he did become doubtful of its creation).

Rhazes believed that the Elixir could be created through the use of four stages. The first stage handled the cleansing of impurities. The second stage reduced the substance to its most elementary states. The third dissolved and recombined the solutions with the use of an acidic catalyst. The fourth combined and solidified the solution into the final form. In this manner, one cannot help but view this Elixir as the Philosopher's Stone that many alchemists sought after.

The Major Divisions

- Mineral - These in turn get divided up into categories.

- Vegetable - Self-explanatory, the plants/flora.

- Animal - Self-explanatory, the animals/fauna.

The Six Minerals

- Spirits - There are 4 of them: arsenic sulphate, sulphur, sal ammoniac, and mercury.

- Bodies - There are 7 of them: Moon, Sun, Venus, Mars, Jupiter, Saturn, and--while not considered a planet--Kharsind or zinc (a metal ruled by Jupiter).

- Stones - There are 13 of them: including magnesia, lapis lazuli, gypsum, azurite, and malachite

- Vitrioles - There are 7 of them: including the colored vitrioles, such as yellow, green, black, white, and red

- Borates - There are 7 of them: including natron and impure sodium borates

- Salts - There are 11 of them: including salt, lime, ash, urine, rock, and naphtha

And from these mineral categories, Rhazes further classified them according to their colors and other characteristics. Pretty comprehensive, huh?

Similar to Avicenna, Rhazes focused on the practicality of his studies. The difference between him and his medicinal contemporary, however, is his main focus, which was still alchemy. Like Avicenna, he did not accept the theory of balance like Geber did. Unlike Avicenna, he believed that the transmutation of metals can still be achieved (though, after some work in attempting to create the Elixir, he did become doubtful of its creation).

Rhazes believed that the Elixir could be created through the use of four stages. The first stage handled the cleansing of impurities. The second stage reduced the substance to its most elementary states. The third dissolved and recombined the solutions with the use of an acidic catalyst. The fourth combined and solidified the solution into the final form. In this manner, one cannot help but view this Elixir as the Philosopher's Stone that many alchemists sought after.

|

Sirr al-Asrar

Sirr al-Asrar, or The Secret, became Rhazes' great work, where he created a more in-depth classification of the substances used within alchemy. Like his previous work, he divided Sirr al-Asrar into three parts:

|

That said, while Rhazes was, indeed, a brilliant mind during his time, he ultimately did not gain the favor and success that he sought during his lifetime. In fact, while Rhazes did for a time live in splendor, his patron, Emir Khorassan of Persia, became displeased with him. After failing to transmute gold for the emir, Rhazes was banished from court, some stories even going to say that he had been blinded after the emir flew into a wild rage. After the transmutation failure, Rhazes lived poorly for the rest of his life.

For your lesson assignment, click here.